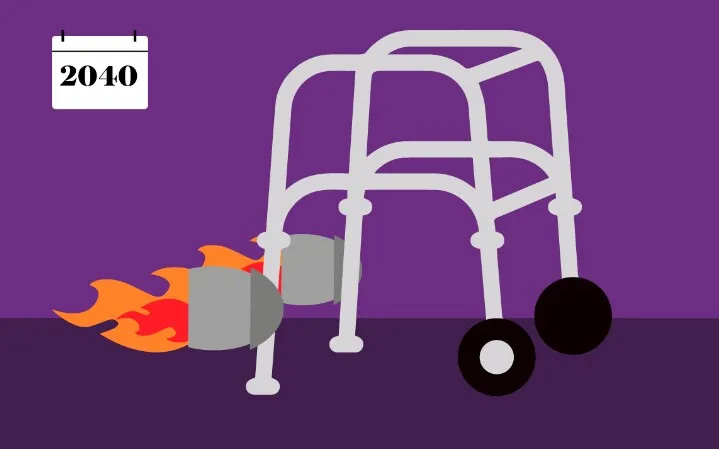

Old age reloaded

Average life expectancy in the West has increased by two years every decade for two centuries, mostly due to declining child mortality. A child born in the First World this year has, by some estimates, more than half a chance of living to be over 105.

That is surprising, entrancing and terrifying all at once. For most of our history we have assumed that our life reaches its prime between 18 and 45 and that we will move linearly through it, as through Shakespeare’s ages, from childhood into dotage. Changing this would transform our society completely. What will that look like?

Economic transformation

For a start it will require a profound transformation of our economy or our welfare state or both. If we’re all going to live twice as long after the current retirement age, we will self-evidently have to work longer, live on less or vastly increase the amount we put aside. Basic income funded by the GDP boost from a bigger workforce, or a much toothier regime of mandatory employee and employer pension contributions, could cover that.

But two-fifths of the NHS budget and 17 per cent of welfare spending already go to over-65s; any solution which has old people further subsisting on the labour of the young will be politically controversial, fiscally dubious and foster intergenerational resentment of the kind which has paralysed Japan.

Another approach is outlined by Andrew Scott and Lynda Gratton in their book The 100-Year Life. They posit a “multi stage” life to replace the “three stage” model – a world in which we flexibly alternate periods of intense devotion to our careers with leisure, part-time-work and child-raising in an order of our choice. Endless reskilling will be normal and you won’t know someone’s age just because they’re a “manager” or an “undergraduate”. We could see the arrested development of millennials extended as education lasts even longer, or an influx of bright-eyed career-switching over-65s into the workforce. Imagine having a strategy meeting with your mother, your daughter and your grandson – not necessarily in that order of seniority.

Social life would change too. We may see a return to the pre-1945 norm of cross-generational friendships, only with positions randomised. Marriage and relationships may loosen: “ ’til death do us part” has a different ring when death is so delayed. And the rise of the active, curious, high-spending pensioner is already a cliché in 2017. In the coming century, gap years, aimless career dabbling and hard drugs may be associated primarily with old age, so bee ready!